I’m Not Broken is a vulnerable memoir of the life of author Jesse Leon, growing up as a Mexican American in San Diego, in the 1970s. Leon opens up about the challenges that he experienced in his childhood, which include sexual abuse, addiction, and prostitution. While Leon unravels his childhood, he also highlights the systemic changes that need to take place, in order to help victims in similar positions. Through all the hardships, Leon was able to find a community that helped him through his challenges and shaped him into a mentor, for others; he even achieved higher education at Harvard University. This memoir captures Leon’s strength, determination, and resiliency against all odds.

Content warning: drug addiction, alcohol addiction, sexual abuse, prostitution, and suicide ideation.

“This memoir captures Leon’s strength, determination, and resiliency against all odds. ”

I was able to interview Jesse Leon on behalf of Latinx In Publishing to discuss I'm Not Broken.

Mariana Felix-Kim (MFK): You were incredibly vulnerable in your memoir and shared multiple impactful stories. What made you decide that it was time to share your stories and how did you decide how vulnerable to be?

Jesse Leon (JL): I believe my book, I’m Not Broken is extremely relevant to what's happening in America today, especially given the issues of substance abuse, addiction, mental health, immigration, sex trafficking, LGBTQ+, and racial justice. I wanted to share my journey, including my vulnerabilities, all of which led me to the steps of Harvard University, so that anyone who is experiencing or has experienced issues with anxiety, accessing mental health services, sex abuse, trauma, identity issues, and/or addiction - and who feel as alone as I once did - that they can identify and realize that they are not alone and find hope. That we can be successful as human beings and as professionals. We can move from surviving to thriving. And most importantly, that our traumas don't define us and that we can be triumphant.

MFK: You overcame many challenges on your own and endured a lot of them in silence. It wasn't until the incident, with the new student, that you were able to open up to someone. It seemed beneficial when you opened up to Officer. In your opinion, what is the best way to offer support to someone who is suffering in silence? How can we make sure more kids have trustworthy adults?

JL: The best way to offer support for someone who is suffering in silence is to build a rapport based on being present, consistent, and communicating that we are here to listen without judgement. This helps build trust. Once someone does open up - listen intently to genuinely hear what they are saying, while allowing for pauses for others to finish their thoughts and to give them the opportunity to assess your reactions for safety. Building trust is key to getting people who have experienced trauma to grow from surviving to thriving.

MFK: A big theme in your memoir is the "otherness" BIPOC communities often feel. I was interested in how you highlighted that when you were working towards becoming sober this actually became a crutch for you. You discuss the different experiences that Hope (a white woman) and you faced. The volleyball day seemed to be a turning point for you because you realized that Narcotics Anonymous (NA) values inclusion. Do you think there is a more effective way to intertwine inclusion in order for participants to feel included sooner or do you think this was part of the journey?

JL: I think this was just part of the journey, at least for me. I had a habit of always focusing on the differences and not the similarities I had with others, whether it was in recovery, in school, at Harvard, etc. Getting to know others on a human level based on similarities and not differences took practice, and with time, I was able to get better at it. This is why ice-breakers and team building activities focused on shared underlying values are important when trying to break down barriers - especially in the workplace. Being able to see the common humanity in each other is a great way to make sure everyone feels included.

MFK: When you were attending your mandatory therapy sessions, you revealed that your therapist was aware of the challenges you were facing and did not help you logistically and emotionally. How can we improve our State Crime Victims Compensations?

JL: I wish the State Crime Victims Compensations board provided information in multiple languages to me as a child and to my parents about our rights and where we could go if we needed help in finding a new therapist, encountered a negative situation with a therapist, and/or had a complaint. I believe the states should provide this resource in multiple languages and that therapists should be required to share this information with their clients at their first meeting, so that clients know where to go for help or to file a complaint if needed. And those concerns or complaints should be followed up confidentially and within a required timeframe. There should be a mechanism in place to follow up with clients to ensure that they are receiving quality access to mental health and if not, re-direct individuals to the appropriate gender affirming and multilingual care. Confidential follow-up, oversight, and accountability is key to improving outcomes for survivors and their families.

MFK: Z's frustration with difficult children came out when he was introduced to you. In your own work, have you experienced the frustration Z had of Latine children satisfying society's stereotype of not caring enough to stay in school? How have you handled it?

JL: Yes, I have, especially when engaged in youth leadership development, alternatives to incarceration programs, or when mentoring young adults. I've handled it by stopping, pausing, taking a deep breath and remembering how I would have liked to have been treated growing up. I realized through journaling and therapy that because of my trauma and my inability to find the words to adequately describe what I was feeling as a child, that too often my reasoning and my emotions were not in balance. My emotions would take over and I would have an overwhelmingly incomprehensible reaction to situations, which I believe occurs with many of our young people today, who sadly experience one of these moments at the most inopportune times and end up incarcerated or penalized. I like to use curious inquiry to truly understand where a person is coming from to help get their emotions and reasoning in balance to reach a successful outcome.

MFK: While attending NA, you mention your journey to get a sponsor. You were interested in asking a Latino man to become your sponsor but were encouraged to ask a Black man since "you already knew how to interact with Latinos". Do you think this decision was the right one? Do you encourage others to pick a sponsor from a different background?

JL: There are many different suggestions on how to pick a sponsor - it just so happened that I came together with mine unexpectedly. He exemplified the saying that we use in NA, that it's not about "age, race, sexual identity, creed, religion, or lack of religion." It’s about finding the sponsor that teaches you to love and respect yourself. That helps make you whole and sets you up to thrive.

MFK: One of my favorite lines in your memoir is "And I felt it was my duty to speak to issues of race and inequality as things that need to be addressed up front and not be add-ons or second thoughts in the creation of public policy". I strongly resonated with this quote and completely agree that race and inequality tend to be a caveat or added later on. For people that might not be in the political or activism sphere, how can we be better allies to support this mission?

I hope that sharing my story will inspire others to promote inclusion, belonging, and understanding that allows people like me to be their authentic selves. I know that if everyone does their part, we can create a world where everyone feels like we can thrive and are not broken.

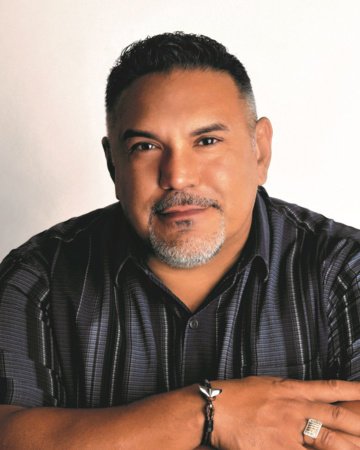

Jesse Leon is a social impact consultant to foundations and investors on ways to address issues of substance abuse/addiction, affordable housing, and mental health. He is a native English and Spanish speaker and fluent in Portuguese. He is an alum of UC Berkeley and Harvard and based in San Diego.

Mariana Felix-Kim (she/her) lives in Washington, D.C. with her lovely cat, Leo. When she is not working in the environmental science field, Mariana is constantly reading. Her favorite genres include non-fiction, thrillers, and contemporary romances. Mariana is half Mexican and half Korean. You can find her on Instagram: @mariana.reads.books